SOVIET RUSSIA. Brief history of the USSR |

RUSSIAN ECONOMY IN YEARS OF CONSCIOUSNESS AND REFORMS

Economic transformations of 1965-1973

|

The decline in production growth associated with the low return on investment, the food crisis of 1962–1964, aggravated by the reformation fever of the last years of NS Khrushchev's rule, led the USSR economy to a pre-crisis state. The discussion in the press of the foundations of the new economic reforms developed by a group of economists under Lieberman’s leadership began in 1962. Administrative reforms replaced the necessary economic transformations. Under these conditions, the economic voluntarism of Khrushchev was made by the technocratic business executives, who rallied around their leader, A. N. Kosygin, who supported the decision of the October 1964 plenum of the Central Committee of the CPSU to resign Khrushchev.

Since 1965, economic reform, conceived during the Khrushchev period, but then curtailed, began to be carried out. The economic reform of 1965 was faced with the same tasks as the Khrushchev reforms: the resolution of the crisis phenomena of the Soviet planned economy. First of all, they meant low return on investment and construction in progress (long-term construction), low labor productivity, lagging behind wage growth, poor quality of goods and their insufficient assortment, the problem of labor resources. However, unlike Khrushchev's transformations, the reforms conceived by the new leadership should not have affected the political foundations of society, without the extremes of the previous decade. The basic principles of the Soviet socialist economy were not questioned: state control over property, centralized planning, control over production indicators, etc. The core of the new political course and economic reform of 1965 was the idea of a long-term and progressive improvement of socialism and course on the stability of management structures. The fundamental economic reforms did not affect the social and political system of society and did not question the mechanism of the party leadership.

The beginning of economic transformation was initiated by the reforms in agriculture - the most critical part of the Soviet economy. At the March 1965 plenum of the Central Committee of the CPSU, Leonid Brezhnev acted as a champion of reform in agriculture. He proposed to increase investment in agriculture while stimulating productivity. In fact, it was an attempt to intensify agriculture. The agrarian sector of the Soviet economy was to receive an additional amount of machinery, fertilizer and electricity. The total amount of investment in agriculture in 1966-1980. made up. 383 billion rubles, more than three times higher than all previous investments in the agricultural sector. A new long-term production planning system was adopted. State farms and collective farms were written off debts, purchase prices were increased, and surcharges were charged up to 50% for over-sales of products to the state, as well as for their quality. For 1965-1977 purchase prices for agricultural products increased by about one and a half times with almost no change in retail prices. Since 1965, the system of lending to collective farms has changed, receiving the possibility of direct bank lending, unlike the previous system of loans through procurement organizations.

The collective farm income tax, now levied on net income, was also reduced.

In the 60-70s. large-scale programs of land reclamation and construction of irrigation canals were proclaimed. stabilization of exploitation of virgin lands and a special plan for the revival of non-chernozem lands of central Russia. The Great Stavropol, North-Crimean, Karakum and other channels were commissioned. In order to raise the living standards of the peasants, collective and state farms received a large economic independence, where cost accounting elements were introduced.

In 1969, 35 years after the previous congress, the III congress of collective farmers took place. A new model charter was approved, which canceled the old system of payment for workdays and introduced a guaranteed monthly payment, while the monetary part of incomes increased in relation to the real payment. The statute enshrined the pensions of collective farmers and the vacation system. The standard of living of the rural population in the 70s. has grown significantly, although it was not possible to eliminate the difference between town and country, every year up to 700 thousand people left the village. The new programs, which made a bet on the growth of capital investments, were in conflict with the previous course of intensive development. By the mid 70s. economic transformations in agriculture became more and more subsidized and extensive.

In parallel with the transformations in agriculture, industrial reform developed. An active role in its development and implementation was played by A. N. Kosygin, who became Chairman of the Council of Ministers on October 15, 1964. The September 1965 plenum of the Central Committee of the CPSU initiated the transformations. The decisions of the plenum determined the three main directions of the reform: changing planned indicators and reporting, expanding the economic independence of enterprises and strengthening the material interest of workers in the results of their work.

The number of planned indicators for enterprises decreased from 30 to 9. In addition to the gross indicator (that is, the cost of production), which previously determined the efficiency of production, a reported indicator of the cost of sales was introduced. The company was now interested not only to produce, but also to sell products. At the same time, the enterprise profitability index was calculated as the ratio of profit to the sum of fixed assets and working capital. It proclaimed the inadmissibility of changing the plan without agreeing with the enterprise, in turn, the enterprise itself could independently distribute the output within the framework of a given plan. Thus, the enterprise received relative production independence in matters of internal planning of output. In order to materially stimulate production, part of the profits of the enterprise remained at its disposal. The enterprises created incentive funds that were used for the development of the company, material incentives for employees, social and cultural events, housing, etc. It was planned to increase the premiums in the event of a planned over-fulfillment of the plan.

In 1966, the transfer of industrial enterprises to new working conditions began. By the end of 1970, out of 49 thousand enterprises, reform affected 41 thousand enterprises to one degree or another. Meanwhile, at the very beginning of the reforms, there was a cooling towards them by the party elite. At the XXIII Congress of the CPSU, which took place in April 1966, the course of economic transformations was only briefly touched upon in the report of Brezhnev. A certain opposition to the reforms came from the ministries that did not want to give up control over enterprises even within the framework provided by the reforms. At the same time, despite the great autonomy of enterprises, the number of ministries in the late 60s - 70s. steadily increased. Only in the machine-building industry in 1965, 8 all-union departments were additionally created, and by the end of 1975 there were already 35 industrial ministries. On July 10, 1967, the “General Provision on the Ministries of the USSR” was adopted, expanding the rights of central authorities.

Many positive reforms with the formal approach of the ministries became an obstacle to the development of production. An example would be the introduction of a solid fee for used production assets, which was not revised depending on the size of the profits. This measure was supposed to encourage enterprises to use their equipment more efficiently, reducing production costs. At the same time, the Ministry of Finance required to pay for all the available (used and unused) equipment at the time of the last audit. If an enterprise got rid of unnecessary equipment, it still paid for it until the next audit. As a result, for the years 1965-1985. the share of equipment replaced due to technological backwardness and wear was reduced almost twice. Serious flaws were also in the top-down rate of return. Ministries and enterprises themselves, as before, determined the prices of their products, artificially overestimating them. Only in mechanical engineering for 1966-1970. wholesale prices increased by 25-30%. The efficiency of the State Committee of Prices formed in 1965, which fought the downfall of the phenomenon, turned out to be low. A different committee created at the same time (Gossnab) directively defined suppliers and consumers for enterprises, narrowing the scope of their independence.

The main reason for the constant failure in the economy remained "departmental". There was practically no serious direct connection between neighboring enterprises and organizations, if they belonged to different ministries. Thus, the expansion of the admitted independence of enterprises was poorly combined with the strengthening of the administrative and economic powers of the departments. The absence of room to move forward was becoming stronger. The unsolved problems accumulated by the end of the Eighth Five-Year Plan created serious blockages and obstacles to the introduction of new methods of planning and management, which led to a crisis situation in the leading sectors of the national economy, to the gradual curtailment of reforms. Although the first two years of economic reform yielded significant results, in the future its effectiveness decreased. The reform touched, first of all, the enterprises, without affecting the top of the economic pyramid: the ministries, the centralization of management and the administrative-command apparatus. Gradually, the rights of enterprises were limited, the number of planned indicators increased, and adjustments to plans became more frequent.

|

|

History of the Soviet Union and Russia in the 20th Century

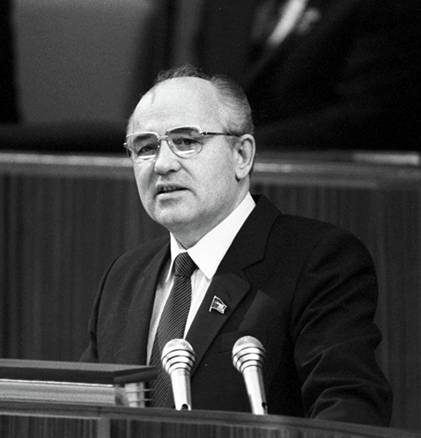

The President of USSR Mikhail Gorbachev